The Rules the Networks Refuse to Follow

Sign up for a six month free

trial of The Stand Magazine!

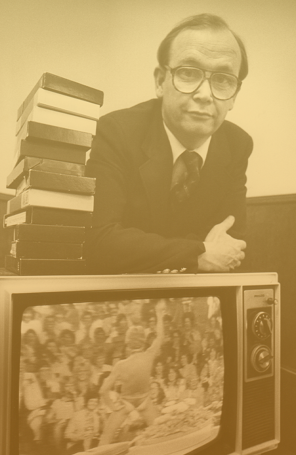

The momentum behind the “Turn the Television Off Week” campaign invigorated Don. The support, the media coverage, the spotlighting of the concern—it all testified to a collective need America was feeling. Lynda Wildmon, Don’s wife, would later reflect on this. “I’ve always heard that a movement won’t catch on unless there’s a need or a desire. And I do think that was the case in this,” she said. “It caught on very quickly.”[1]

To this point, Don’s research had mostly looked at the negative effects of television violence. But as February progressed, he honed his focus to try and understand the medium itself—and, in particular, the business infrastructure behind it. What is television broadcasting and how does it function?

As he read the Communications Act of 1934 and other key documents regulating broadcasting, he was surprised to learn that every American citizen is a partial owner of the TV airwaves—the space in which televisions transmit their signals. Even more, every ABC, CBS, and NBC station affiliate is licensed by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). This license—which must be periodically renewed—grants the broadcaster the privilege to use these publicly owned airwaves free of charge while also stipulating that the licensee must continue to “serve the public interest.

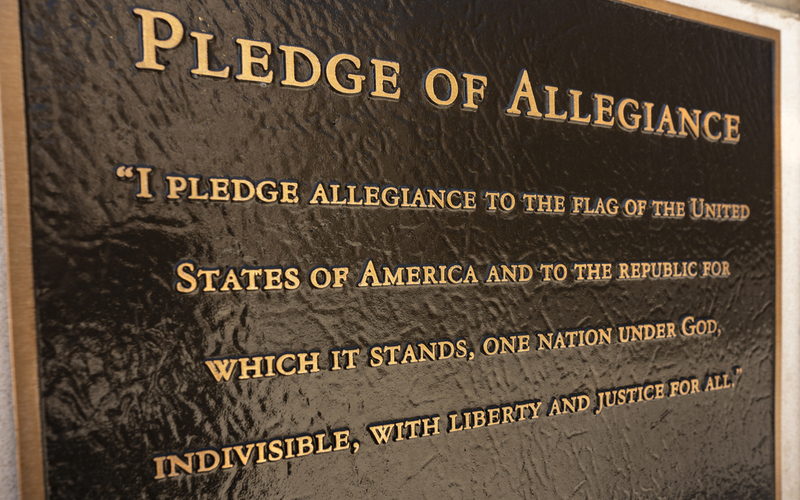

“In other words,” Don said, “the entire television industry has a mandated obligation to provide satisfactory programming in the interest of the public it serves.”[2] But how does one define the public interest? As nebulous as that term may seem, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) defined it in very concrete, ethical terms. It was called The Television Code.

As television was emerging on the national scene, the NAB drafted The Television Code to remind broadcasters of the high responsibility of having direct, intimate access to American homes. This code of ethics outlined acceptable program material—defining what it meant to provide “wholesome entertainment” that would also remind a viewer of “the responsibilities the citizen has towards his society.”

· “Profanity, obscenity, smut, and vulgarity” were explicitly forbidden.

· Drunkenness and drug use were never to be “presented as desirable or prevalent.”

· Legal and medical advice should always conform to recognized ethical standards.

· Cruelty, greed, and selfishness should not be presented as “worthy motivations” for human achievement.

· Criminal acts were not to be shown in such detail so as to encourage imitation.

· “Respect is maintained for the sanctity of marriage and the value of the home.”

· “Illicit sexual relations are not to be treated as commendable.”

· Costumes, camera angles, and actor’s movements were not to be used to emphasize “anatomical detail as would embarrass or offend home viewers.”

In addition to the content of programming, the code was equally concerned with the tone of material presented.

· Racial and nationality types were not to be a means to ridicule the particular race or nationality depicted.

· Special precaution was to be given to showing those suffering from physical and mental afflictions.

· Religion and religious faith were not to be attacked.

· “Reverence is to mark any mention of God, His attributes and powers.”

The code also reminded broadcasters of the particular responsibility they had toward children.[3]

The code was signed by all three television networks on March 1, 1952, in order to cooperatively “maintain a level of television programming which gives full consideration to the educational, informational, cultural, economic, moral and entertainment needs of the American public to the end that more and more people will be better served.”[4] The code also acknowledged that viewers should be encouraged to make their criticisms and suggestions known to TV broadcasters.

On the 25th anniversary of the ratification of The Television Code—March 1, 1977—Donald Wildmon announced the formation of a new citizens’ action group: the National Federation for Decency. The date was not a coincidence. As Don said at the press conference at First United Methodist Church in Southaven, the standards outlined in the 1952 code had “consistently deteriorated” through the years. Now it was a shock to read that the networks claimed to abide by them at all.

The focus of the group was simple: the National Federation for Decency was going to monitor television and hold the networks accountable to their agreement to maintain decency and the public interest. When they failed, the NFD was prepared to coordinate a public response.

After some preliminary TV monitoring, NBC was found to be the worst offender. They would also be the first target of the NFD. The Methodist preacher from Mississippi was stepping out of the safety of his local church and into the highly-contested arena of corporate boardrooms. The stage was set. The terms were clear. The battle was just beginning.

This is the third part of an on-going series of historical snapshots from the history of AFA. To watch the documentary Culture Warrior: Don Wildmon and the Battle for Decency for FREE, go to culturewarrior.movie.

[1] Lynda Wildmon transcript, recorded for Culture Warrior (American Family Studios, 2023), 6.

[2] Donald E. Wildmon with Randall Nulton, The Man the Networks Love to Hate (Wilmore, KY: Bristol Books, 1989), 38.

[3] The Television Code of The National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters (Washington, D.C.: NARTB, 1952), 2–3.

[4] The Television Code of The National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters (Washington, D.C.: NARTB, 1952), 8.

Sign up for a free six-month trial of

The Stand Magazine!

Sign up for free to receive notable blogs delivered to your email weekly.