The Horrors of War...

Sign up for a six month free

trial of The Stand Magazine!

(Editor's Note: This article first appeared in the August 2022 print edition of The Stand.)

“Over this spot on 2 September 1945, the instrument of formal surrender of Japan to the Allied Powers was signed, thus bringing to a close the second World War.”

These words are inscribed on a plaque found on the deck of the USS Missouri, forever marking the historic location of one of the most monumental moments in U.S. history. The date is often called V-J Day, Victory over Japan Day.

Just a few months prior, on May 8, 1945, the official surrender of German forces in the European theater of conflict was accepted by the Allied Powers. Yet the jubilation was tempered by the fact that although Hitler was dead, and Germany had surrendered, on the Pacific front, Japan showed no sign of letting up.

Four years earlier, Japan had drawn the U.S. into the global conflict with a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Changing loyalties

Through the late 19th and early 20th centuries, U.S. and Japanese relations were amicable but competitive, both countries vying for influence in eastern Asia.

Over time, and during industrialization and rapid expansion, Japan’s military grew more powerful and effectively gained control of the government. Western countries like the U.S. had established colonies in Asia to secure natural resources and markets, and Japan, now being run mostly by its army, had a desire to do the same.

This led Japan to invade surrounding territories, mostly China, committing terrible atrocities along the way. For example, in a December 1937 incident known as the Nanjing Massacre, or the Rape Of Nanjing, it is estimated that some 150,000 male war prisoners as well as an additional 50,000 male civilians were murdered, along with 20,000 women and girls brutally raped and then killed.

Despite a longstanding friendship with China, the U.S. hoped to remain neutral and avoid getting engaged in a conflict with Japan. But as people became aware of Japanese tactics, public opinion began to shift, favoring China.

By 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt began to simultaneously grant aid to China and tighten restrictions on Japan, which depended on the U.S. as its main supplier of oil, steel, iron and other commodities.

Tensions increased between the U.S. and Japan, and by mid-1941, the U.S. had placed a full embargo on Japan, stopped all negotiations with Japanese diplomats, and frozen Japanese assets in U.S banks.

A few months later, Japan launched its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. The very next day, December 8, 1941, the U.S. declared war on Japan. Subsequently, Japan’s ally, Germany, declared war on the U.S., plunging the U.S. into the global conflict. From 1942 through 1944, Allied Powers waged an effective war against Japan in the Pacific.

Calling for surrender

On July 26, 1945, Allied leaders issued the Potsdam Declaration, calling on Japan to surrender and promising Allied troop withdrawal and self-governance once the conditions were met. The document warned, “The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

Still, Japan refused to give up. Thus, on August 6, 1945, American forces dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, killing 70,000 or more people and destroying a five-square-mile portion of the city. Just three days later, Nagasaki was the site of a second atomic bomb, killing another estimated 40,000.

The overwhelming force broke the Japanese government, and the day after the Nagasaki attack, it issued a statement accepting the terms of the Potsdam Declaration. On August 15 (August 14 U.S. time), by way of a radio address, Japan’s Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender. Thus in the U.S., August 14 is often cited as V-J Day.

At war’s end, Japanese deaths numbered 2.6+ million. U.S. deaths attributed to the war are estimated at more than 400,000.

Today, the USS Missouri rests as a memorial in Pearl Harbor, a tribute to victory, yet a somber reminder of the costs of war.

… the heart of a warrior

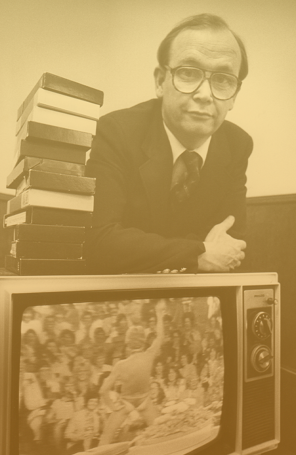

At age 18, Mississippi native Thomas Earl Griffin witnessed firsthand the aftermath of the bombings of Japan. At 95 today, he still recalls vividly his time in Japan.

“I was drafted in 1945,” Griffin told The Stand. “As soon as I finished basic training in Camp Gordon, Georgia, I received orders to report to Fort Ord, California, in 10 days, and the military didn’t provide a way. I had to get there on my own.”

Griffin recalls knowing that Japan was his ultimate destination. The U.S. was planning a land invasion if the Japanese didn’t surrender. A government report later estimated that had the war continued, it would have lasted another 18 months, with an estimated 5 to 10 million more Japanese deaths, and 1.7 to 4 million more Allied casualties.

“I was sitting on a pier in San Pedro, California, waiting to board a ship that was battle ready,” Griffin said. “In the mean- time, they dropped the atomic bombs. If they hadn’t done that, I probably wouldn’t be here today.”

Griffin’s outfit was among the first there, arriving only days after the bombings. “There were 18 or 20 of us detailed to guard the military and civilian leaders facing war crime charges,” Griffin said.

Griffin guarded and transported some notable war criminals.

“We had the general that led the Bataan death march as well as one of the Japanese soldiers accused of beheading those Doolittle Raiders,” he said.

Griffin recalls few prisoners’ names, but does recall Prime Minister General Hideki Tojo, likely the most prominent of the Japanese war criminals.

Griffin was surprised by the prisoners’ attitudes. “They didn’t have any remorse for what they had done,” he said. “They thought they were doing what the emperor wanted them to do. They thought they were right.”

Another haunting memory is the devastation at the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bomb sites.

“I went through where they dropped the bombs several times. There was nothing left. There may be a steel beam sticking up here and there, but it was all gone. It was as if everything just disappeared,” Griffin said. “When the Allied powers promised utter destruction, they meant it and accomplished it. I don’t guess there was a living thing left.”

Griffin’s wife of 74 years, Maurice, chimed in and shared her own recollection of V-J Day. “In our small town of Vardaman, Mississippi, both the Methodist and Baptist churches rang their bells all day in celebration of Japan’s surrender,” she said.

“And then the following Sunday, the churches were full of people gathering in thankfulness that the war was over.”

Sign up for a free six-month trial of

The Stand Magazine!

Sign up for free to receive notable blogs delivered to your email weekly.