Kamala Harris Is Not Eligible to Be Vice-President of the United States

Sign up for a six month free

trial of The Stand Magazine!

The Constitution says that a vice-president must meet the same eligibility requirements as the president: "[N]o person constitutionally ineligible to the office of President shall be eligible to that of Vice-President of the United States." Article II of the Constitution specifies "[n]o person except a natural born citizen...shall be eligible to the office of President."

Senator Kamala Harris is not, from a constitutional standpoint, a natural-born citizen of the United States. She was born on American soil, but that’s not enough to qualify for birthright citizenship. Here is the actual language of the 14th Amendment (emphasis mine throughout):“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” It’s not enough just to be born on U.S. soil. You must both be born on U.S. soil and be subject “to the jurisdiction thereof” when it happens.

It’s not even enough that one’s parents be legally present in the U.S. at the time of the child’s birth. The issue is to whom do the parents - and therefore the child - owe their ultimate allegiance. So while they may temporarily be subject to the jurisdiction of the U.S., their ultimate allegiance, the ultimate jurisdiction to which they are subject, belongs to the nation of their birth, the land where they possess citizenship and from whence they came.

Sen. Harris’ father is a Jamaican national and her mother is from India, and neither was a naturalized U.S. citizen at the time of Harris' birth in 1964. In fact, neither of them was even a “lawful permanent resident” of the U.S. at the time. This means that she is not a "natural born citizen"—and therefore this also means she is ineligible for the office of vice-president.

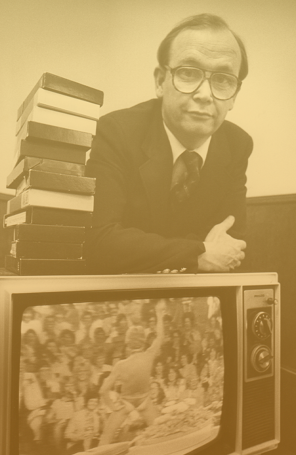

John Eastman is one of the most distinguished constitutional law experts in America. He is a professor of law at Chapman University and a senior fellow at the Claremont Institute. The phrase “subject to the jurisdiction” means, he writes, “subject to the complete jurisdiction, not merely a partial jurisdiction such as that which applies to anyone temporarily sojourning in the United States (whether lawfully or unlawfully).”

Thus the fact that her parents were sojourning here legally is not decisive. The issue is not location, it is citizenship.

While most Americans, untrained in the Constitution, believe that anyone born on U.S soil is automatically a citizen, this is actually a new idea, unheard of until the late 1960s. As Eastman points out, “the Supreme Court has never held that anyone born on U.S. soil, no matter the circumstances of the parents, is automatically a U.S. citizen.” Birthright citizenship only belongs to those whose parents were subject to the jurisdiction of the United States the moment they were born.

For example, children born in the U.S. to guest workers from Mexico during the 1920s were not regarded as citizens, nor were children born to guest workers in the bracero program of the 1950s and early 1960s.

Diplomats are “subject to the jurisdiction” of their homeland. That’s why children born to diplomats in the U.S. are not citizens of the United States. Legally and constitutionally, their children are no more “subject to the jurisdiction” of the U.S. than their parents are. If a child’s parents are not American citizens when the child is born, neither is the child.

Diplomats often use the concept of “diplomatic immunity” to get themselves and their children out of trouble on American soil by claiming that the children are not under the authority, or “jurisdiction,” of American law. All the American government can do in such circumstances is send them back to their home country. We can’t lock them up; all we can do if they misbehave is deport them.

It’s worthy of note that the word “diplomat” is not in the 14th Amendment. The children of a diplomat are not regarded as citizens by birth. This is not because their father is a diplomat, but because he is a citizen of a foreign country. Since the parents are not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States, neither are the children.

The logic is inescapable. If the children of foreign diplomats are not U.S. citizens by birth, how is it possible that children of temporary residents or illegal aliens could be?

A key question has to do with the precise meaning of the Jurisdiction Clause in 1868 when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified. The best tool for answering that question is to look at the Civil Rights Act (CRA) of 1866, enacted the same year that the Fourteenth Amendment was written by Congress.

The 14th Amendment was intended, in fact, to elevate the provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 to constitutional status and insulate it from legal challenge.

The Civil Rights Act included a provision to secure citizenship for former slaves, to nullify the infamous Dred Scott opinion. The provision read, “All persons born in the United States, and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States.”

According to the CRA, Indians who were not taxed were not eligible for citizenship. The reason they weren’t taxed by the United States was that they were subject to the “foreign power” of the sovereign Indian nations to which they belonged.

As Ken Kuklowski puts it, “The Fourteenth Amendment only commands citizenship to persons born on U.S. soil to parents who are not citizens of a foreign country.”

Rep. John Bingham of Ohio, considered the father of the 14th Amendment, explained the language of the amendment this way: “every human being born within the jurisdiction of the United States of parents not owing allegiance to any foreign sovereignty is, in the language of your constitution itself, a natural born citizen.”

The “Jurisdiction” clause was added to the 14th Amendment only after a lengthy debate. According to NumbersUSA, Sen. Jacob Howard of Michigan proposed the amendment because he wanted to make it clear that the simple accident of birth on U.S. soil was not in fact enough to confer citizenship.

Sen. Howard said the jurisdiction requirement is “simply declaratory of what I regard as the law of the land already,” a reference to the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

In his debate, Sen. Howard said, "[T]his will not, of course, include persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers accredited to the Government of the United States.”

Here is a great question: if citizenship was granted by birth alone, why did it take an act of Congress in 1922 - 54 years after the ratification of the 14th Amendment - to grant citizenship to American Indians, every one of whom had been born on American soil?

Since 1795, aliens have been required to renounce allegiance to any foreign power and declare allegiance to the U.S. Constitution to become a naturalized citizen. Such allegiance was never assumed for aliens who were born here or migrated here. We have a framed copy of my great-grandfather’s renunciation of his allegiance to the Czar of Russia as a family heirloom. That renunciation was a prerequisite to his being granted full citizenship in the United States.

The way forward is simple. Section 5 of the 14th Amendment gives power to Congress to “enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.”

Some well-meaning Republican candidates are calling for an amendment to the Constitution to ban birthright citizenship. But in truth, the Constitution does NOT need to be amended. It only needs to be applied.

Bottom line: Are children of foreign sojourners American citizens? No. Why? Because the Constitution says they aren’t.

As realists, none of us expect that anything will come of all this. We long ago as a nation decided that we will not be troubled by the parts of the Constitution that are inconvenient. But perhaps it's time we started following the whole thing, not just the parts we happen to like. Kamala Harris is as good a place as any to start.

Sign up for a free six-month trial of

The Stand Magazine!

Sign up for free to receive notable blogs delivered to your email weekly.