Why “National Socialism and Christianity Are Irreconcilable”

Sign up for a six month free

trial of The Stand Magazine!

Born on November 10, 1483, in Eisleben, a small town in the state of Saxony [now central-eastern Germany], an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire, Martin Luther (1483-1546] was a theologian, composer, pastor, and monk. One of both Western and church history’s most significant figures, Luther played a key role in the Protestant Reformation, providing a case in point to King David’s query in Psalm 11:3: “If the foundations are destroyed, what can the righteous do?”

Ordained to the priesthood in 1507 and spending his early years in relative anonymity as a monk and scholar, Luther came to prominence in 1517 with the publication of his Ninety-five Theses, setting out a devastating critique of the church’s sale of indulgences [i.e. certificates of forgiveness] and explaining the fundamentals of justification by grace alone.

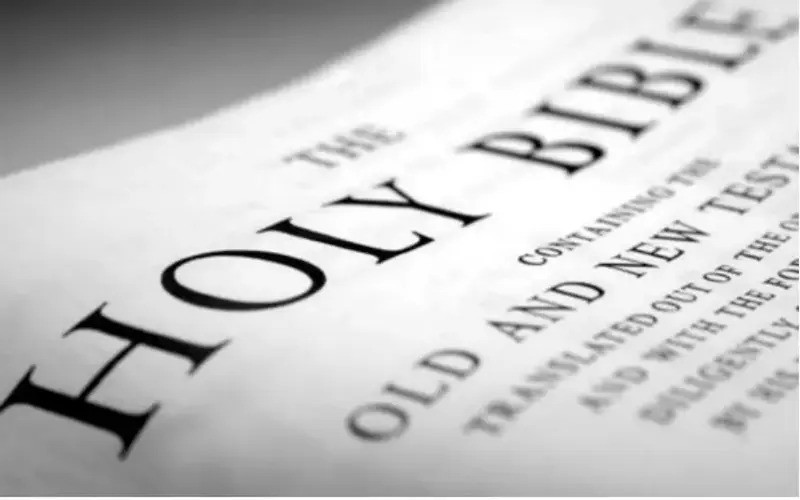

Prior to his Ninety-five Theses, Luther had already translated parts of the Bible, such as the penitential psalms, the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer and the Magnificat [Mary’s Song of Praise, 1 Luke 1:46-55].

Luther deemed the Bible alone [sola scriptura] to be the ultimate authority for faith and practice. Regarding justification, he understood that “we are saved solely through faith in Jesus Christ because of God’s grace and Christ’s merit. We are neither saved by our merits nor declared righteous by our good works. Additionally, we need to fully trust in God to save us from our sins, rather than relying partly on our own self-improvement.”

With the translation of the entire Bible, a work completed in 1534, Luther accomplished something “cataclysmic,” in the view of Eric Metaxas in his New York Times bestseller, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy.

While the word cataclysmic generally carries a ruinous, harmful implication, in Metaxas’ application it refers to the common man in Germany coming alive to the Word of God, which then transformed culture. It validated Jesus’ guarantee in John 8:32: “You will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.”

The simple rendering of the Word transformed “traditional Western moral and legal philosophy by making not reason but the Bible, and more particularly the Ten Commandments, the basic source and summary of natural law,” wrote Harold J. Berman in his classic Law and Revolution, II: The Impact of the Protestant Reformations on the Western Legal Tradition.

Over the next two centuries, Christian focus in post-Lutheran German culture unfortunately began to fade. The key figures in the new movement were Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller [1759-1805], German poet, philosopher, physician, historian and playwright, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe [1749-1832], German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, critic, and amateur artist. Both became recognized as the greatest German literary figures of the modern era.

In a sense, their literary and cultural crusade led to secularization in the period known as “Weimar Classicism,” relating to or concerned with the physical or material world, as opposed to a spiritual one. On full display, German government-run education came to be captured by secularists. Interestingly, both Schiller and Goethe were reared in Lutheran Christian homes and spent their early years studying Scripture.

Fast forward to early 20th-century Germany, where, as Metaxas elucidates, “On January 30, 1933, at noon, Adolf Hitler became democratically elected chancellor of Germany. The land of Goethe, Schiller, and Bach would now be led by someone who consorted with crazies and criminals, who was often seen carrying a dog whip in public. The Third Reich had begun.”

German culture, once decidedly Christian, was hailed as the world’s most enlightened and profound. Next, Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler [1889-1945] began slowly but surely eradicating anything Christian. His personal secretary, Martin Bormann [1900-1945], head of the Nazi Party Chancellery, let carelessly or unintentionally slip that “National Socialism and Christianity are irreconcilable.” It revealed the real nature of the cultural war in Germany.

Bormann’s disclosure underscores the spiritual nature of the battle for the soul of Germany and Hitler’s lust for world domination. It also accentuates Solomon’s argument in Proverbs 29:2 that “when the wicked rule [in power and control of the affairs of state], the people groan.”

The Nazi repression of Christianity resulted in “modernizing” the German calendar to devalue Christian celebrations and feasts, banning of carols and nativity scenes in schools, and replacing Christmas with “Yuletide.”3 [The pagan celebration of Winter Solstice, known as Yule, by Germanic peoples.]

Germany had forsaken God, squandering its Christian heritage and biblically based culture. Rather than by natural lapses of memory, it had done so by willful neglect and indifferent impassivity, disregarding willingly the reality of God’s enduring edict that a nation’s greatness is dependent on its piety and ethics, not on its military mettle, erudite elitism or monetary magnitude.

Friedrich Schiller’s observation of the Thirty Years’ War [1618-1648] can likewise be applied to his spiritual stewardship of late 18th-century Germany: “History brought forth a great moment, but the moment found a mediocre people.”

A fitting comment is presented by Peter Leithart in his work A Son to Me: An Exposition of 1 & 2 Samuel: “Goliath’s armor is given unusually detailed attention. We never learn anything about David’s armor after he became king. 1 Samuel 17:5 says that the Philistine giant was wearing ‘scale armor’, and the Hebrew word simply means ‘scales’. This sort of armor is attested throughout the ancient Near East, but the fact that he is described as wearing ‘scales’ indicates that Goliath was a serpent.”

If America is to survive, Christians should begin to function in the public square as vanguards of Jesus’ kingdom assignment provided in Matthew 16:18: “I also tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my ekklesia [assembly in the pubic square], and the gates of Hades will not overcome it.”

Praise be to God that Gideons and Rahabs are entering the public square.

Sign up for a free six-month trial of

The Stand Magazine!

Sign up for free to receive notable blogs delivered to your email weekly.