No, We Do Not Have Too Many People

Sign up for a six month free

trial of The Stand Magazine!

It’s common to hear misguided environmentalists whine and moan about how there are just too many people and the earth is running out of resources to sustain them all. Don’t let them lie to you. They are dead, flat wrong.

If anything, the problem is that we have too few people. The more human beings there are, the more human capital there is to innovate, create, and produce. A simple way to measure productivity and abundance is the price of basic commodities. Based on the fundamental law of supply and demand, as supply goes up, demand and prices go down. When supply goes down, prices go up as dollars chase shrinking supply.

Thus tracking the price of commodities is a foolproof way to measure abundance. If the earth is experiencing an abundance of supply, commodity prices will come down. But if, as environmentalists want us to believe, we are running out of life’s essentials, prices will be climbing like a moon launch.

Cato Institute research reveals that the more the population grows, the more commodity prices drop. In fact, commodity prices dropped 65% between 1980 and 2017. Humans are in truth experiencing not scarcity but a superabundance of life’s necessities as the population grows.

The planet’s resources have become 380% more abundant - not less - over the last 40 years. And Cato predicts prices will drop another 37% over the next several decades.

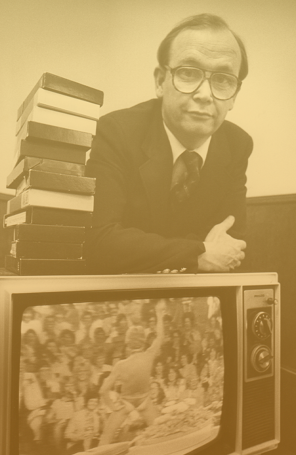

Paul Ehrlich, the author of The Population Bomb (he was a professor at Stanford when I was doing my undergraduate work there) fed off man’s natural pessimism to persuade people that we were doomed by our growing population. Economist Julian Simon argued just the opposite. His view was that as the population grew, more and more people came into the world with the ingenuity to solve problems of production and make more resources available for everybody at a cheaper price.

They made a famous wager in 1980 about the price of a “basket” of raw materials that Ehrlich was convinced would become scarcer and more expensive over the next decade. (Ehrlich had the home-field advantage here - he handpicked all the commodities in the basket.) To win the wager, prices had to go up for Ehrlich to win and down for Simon to win.

In spite of population growth of 873 million people over that decade, Ehrlich lost the bet. All five commodities he had selected declined in price, by an average of 57.6%. Ehrlich had to mail Simon a check for $576.07.

Two researchers concluded that Simon would have won the same bet “in every year from 1980 to 2015.”

In 2010, an international incident was touched off when the Japanese Coast Guard detained the captain of a Chinese vessel after a collision. China retaliated by halting all shipments of rare earth minerals to Japan. China at that time accounted for 97% of all rare earth minerals, which are used in defense systems, wind energy, and electric car production.

As Simon’s model predicted, enterprising people found a way. Some used legal loopholes found ways to make their products with smaller amounts of the elements, and discovered that they did not need rare earths - they were only using them because they were relatively inexpensive.

Companies around the world launched new mining projects, expanded existing plant capacities, and recycled rare earths. The price soon came down after an initial spike.

Then in 2018, Japanese scientists discovered a 16-million-ton patch of minerals in deep-sea mud 790 miles off the Japanese coast. The patch seems to contain a boat-load of rare-earth elements, “including 780 years’ worth of yttrium, 620 years’ worth of europium, 420 years’ worth of terbium, and 730 years’ worth of dysprosium.” The scientists who found this deposit concluded that it “has the potential to supply these materials on a semi-infinite basis to the world.”

The writers of the Cato Institute piece, Gale L. Pooley and Marian L. Tupy, selected a basket of 50 commodities including food, energy, raw materials, and precious metals. They discovered that between 1980 and 2017 the price of these commodities, adjusted for inflation, dropped by 36.3%, while the global real hourly income grew by 80.1%. Commodities that took 60 minutes of work to buy in 1980 took only 21 minutes of work to buy in 2017.

While most people assume that population growth leads to a depletion of resources, the truth is the other way round. Because of the contributions made by every human born on the planet, commodities are more plentiful today because of population growth, not in spite of it. In fact, “Between 1980 and 2017, resource availability increased at a compounded annual growth rate of 4.32 percent. That means that the Earth was 379.6 percent more abundant in 2017 than it was in 1980.”

The authors conclude this way:

“The instrument (the piano) has only 88 notes, but those notes can be played in a nearly infinite variety of ways. The same applies to our planet. The Earth’s atoms may be fixed, but the possible combinations of those atoms are infinite. What matters, then, is not the physical limits of our planet, but human freedom to experiment and reimagine the use of resources that we have.”

Do we have too many people on planet Earth? Nope. In fact, we don’t have enough. It’s time to be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth. Get busy.

Sign up for a free six-month trial of

The Stand Magazine!

Sign up for free to receive notable blogs delivered to your email weekly.