The Decay of Greatness

Sign up for a six month free

trial of The Stand Magazine!

Nations rise and fall. Greatness comes and recedes. A people at any given time may have their exalted place on the world stage but are only too soon replaced by another.

For most people, these are truisms – statements that are so obviously true and repeated so often that they become trite expressions about history and political reality.

C.S. Lewis pithily noted this persistent pattern in Mere Christianity: “Terrific energy is expended – civilizations are built up – excellent institutions devised, but each time something goes wrong. Some fatal flaw always brings the selfish and cruel people to the top, and it all slides back into misery and ruin.”

How many people, however, give serious thought to the question of why this process occurs repeatedly? More importantly, is it happening right now – to our own nation?

A theory of corruption

Some secular sociologists and historians have attempted to unlock the keys of this rise-and-fall pattern.

For his 1934 classic work Sex and Culture, British anthropologist J.D. Unwin studied 80 societies, analyzing their cultural beliefs and practices, especially as related to sex and marriage. This study included the primitive societies of history and his own time, as well as ancient cultures like the Sumerians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, English, and others.

Unwin examined the “cultural condition” of these societies, by which he meant the developmental status and energy they manifested. Was the culture growing – demonstrating what he called “expansive energy?” Then, later in its history, was it improving what it had built – what he called “productive energy?”

Whether or not a society had moved from an uncivilized state to a civilized state and whether it was manifesting creative energy was a direct product, Unwin said, of how sexually permissive the culture was. He defined this by various degrees of “sexual opportunity.” The more sexual opportunity a society’s people had – that is, the fewer restraints placed upon sexual habits – the less energetic it would be.

Penalties for breaching the moral code might take the form of cultural disapproval, punishment, banishment, or even death. Together, the variations of social opprobrium limited sexual opportunity.

These restraints were normally tied to marriage, and the historical evidence showed that absolutely monogamous cultures were the strongest.

“In the records of history, indeed, there is no example of a society displaying great energy for any appreciable period unless it has been absolutely monogamous,” Unwin said. “Moreover, I do not know of a case in which an absolutely monogamous society has failed to display great energy.”

On the positive side of this theory, Unwin argued that limiting sexual opportunity in a society allowed energy to be directed toward creative ends. Creativity required “sacrifices in the gratification of innate desires,” he said.

“[T]he placing of a compulsory check upon the sexual impulses, that is, a limitation of sexual opportunity, produces thought, reflection, and energy,” Unwin insisted.

On the negative side, however, was what happened when a people began to transgress their own moral codes – when sexual opportunity began to be extended in both premarital and extra-marital sexual freedom. Across the board, Unwin found, such cultures began to decay.

In his 1956 work, The American Sex Revolution, Pitirim A. Sorokin, who founded the sociology department at Harvard University, examined this phenomenon as well. He explained:

Since a disorderly sexual life tends to undermine the physical and mental health, the morality, and the creativity of its devotees, it has a similar effect upon a society that is composed largely of profligates. And the greater the number of profligates, and the more debauched their behavior, the graver are the consequences for the whole society. And if sexual anarchists compose any considerable proportion of its membership, they eventually destroy the society itself.

Dissipation as a lifestyle

Sexual laxness appears to be a marker of deeper problems within a culture, and it is probably these issues that begin the process of corruption.

From a Christian perspective on human nature, it makes sense to suggest that when a people stop focusing on their own sensual gratification – including, of course, sex – they have energy and interest in learning and accomplishing other things.

When energy is expended outwardly, self-discipline is exerted to achieve the envisioned goals. It is easy to gratify every desire immediately, but it takes self-control to corral those desires and channel them in ways that benefit society. That means the society that is restricting its desires and keeping them in their proper place is likely to also possess the self-discipline to work in the lab to develop a better light bulb rather than watch movies every night.

Success and progress require hard work, but so does the creation and maintenance of a civil society. In One Nation, Two Cultures, historian Gertrude Himmelfarb said a society’s common values and virtues have “a stabilizing, socializing, and moralizing effect” on the culture.

In free societies like our own, of course, stabilization and moral consensus come at a cost. Like any purchase there is a trade-off – i.e., as Himmelfarb insisted, a “bargain” is struck: “the purchase of stability and morality at the cost of restrictions on liberty.”

These “restrictions on liberty” do not imply totalitarianism but instead refer to the voluntary restriction of personal freedom in order to walk according to a corporate sense of propriety. Instead of a person choosing to blurt out profanity in public, for example, he chooses to restrain himself due to being in what we used to call “polite company.” Civil order is maintained at the expense of the person doing whatever he wants – i.e., at the expense of liberty.

When success is achieved in a culture, however, the process of outward expansion can begin to wane. The fruits are enjoyed, and now the energy is expended ‘inwardly’ on self-gratification, and the culture becomes self-centered and weak. The individual considers his own appetites and the unhindered expression of his own liberty as the highest goods.

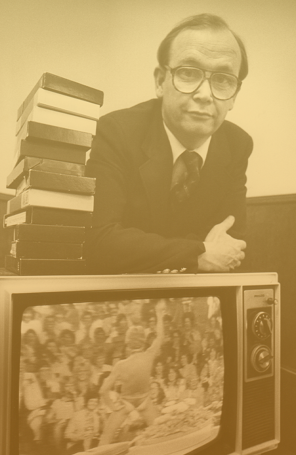

Thus, it is not simply sexual dissipation that is causing less energy, but dissipation itself as a lifestyle – i.e. the life of luxury and distraction. This is the core argument made by cultural critic Neil Postman in his fascinating book Amusing Ourselves to Death. His title is self-explanatory.

In 1992, Vaclav Havel, who was at that time president of Czechoslovakia, wrote about what was happening to his countrymen after they had been liberated from the bondage of a totalitarian communist regime. With no outward pressure to conform to enforced societal norms, he said his fellow Czechs “became morally unhinged.”

Havel said this resulted in “an enormous and blindingly visible explosion of every imaginable human vice.” He continued:

A wide range of questionable or at least ambivalent human tendencies … has suddenly been liberated, as it were, from its straitjacket and given free rein at last. … Thus we are witnesses to a bizarre state of affairs: Society has freed itself, true, but in some ways, it behaves worse than when it was in chains.

It’s almost as if human nature cannot stand success. When men and women prevail over nature or difficult circumstances, or when they accomplish their goals through energetic endeavor, their baser nature eventually seems to arise. Triumph and success provide luxury, which breeds avarice, sensuality, complacency, laziness, weakness, and then decay.

Editor’s Note: This is the first post of a three-part series about cultural decay and renewal.

Sign up for a free six-month trial of

The Stand Magazine!

Sign up for free to receive notable blogs delivered to your email weekly.